The Dartmouth Conference: Cradle of Artificial Intelligence

In the summer of 1956, the campus of Dartmouth College in New Hampshire was quiet — except in one small room. There, a group of scientists and mathematicians had gathered to explore an idea that felt almost daring: Could a machine be made to think?

They weren’t meeting to talk about faster calculators or bigger data storage. They were there to ask whether machines could someday reason, learn, and even understand the world in ways that might rival human intelligence.

From Turing’s Challenge to a Summer in Hanover

Six years earlier, in 1950, British mathematician Alan Turing posed a question that would ripple through the scientific world: “Can machines think?” His paper in Mind didn’t just raise a question — it proposed a test. The “imitation game,” now known as the Turing Test, suggested that if a machine could hold a conversation indistinguishable from a human’s, we might have to admit it was “thinking.”

For many people, this idea was just a thought experiment, something to debate over coffee. But for a handful of ambitious researchers, including John McCarthy, Marvin Minsky, Claude Shannon, and Nathaniel Rochester, it was a challenge worth answering.

Turing’s framing was radical because it sidestepped philosophical arguments about the soul or consciousness. Instead, it offered something measurable. Could you build a machine that responded like a person? Could it learn, adapt, and reason — not in theory, but in practice?

By 1955, McCarthy had grown convinced that the time had come to move from theory to action. Computers were still room-sized and painfully slow by modern standards, but they could already perform complex calculations and store programs. The group believed these machines could, with the right logic and clever programming, demonstrate the first signs of “intelligence.”

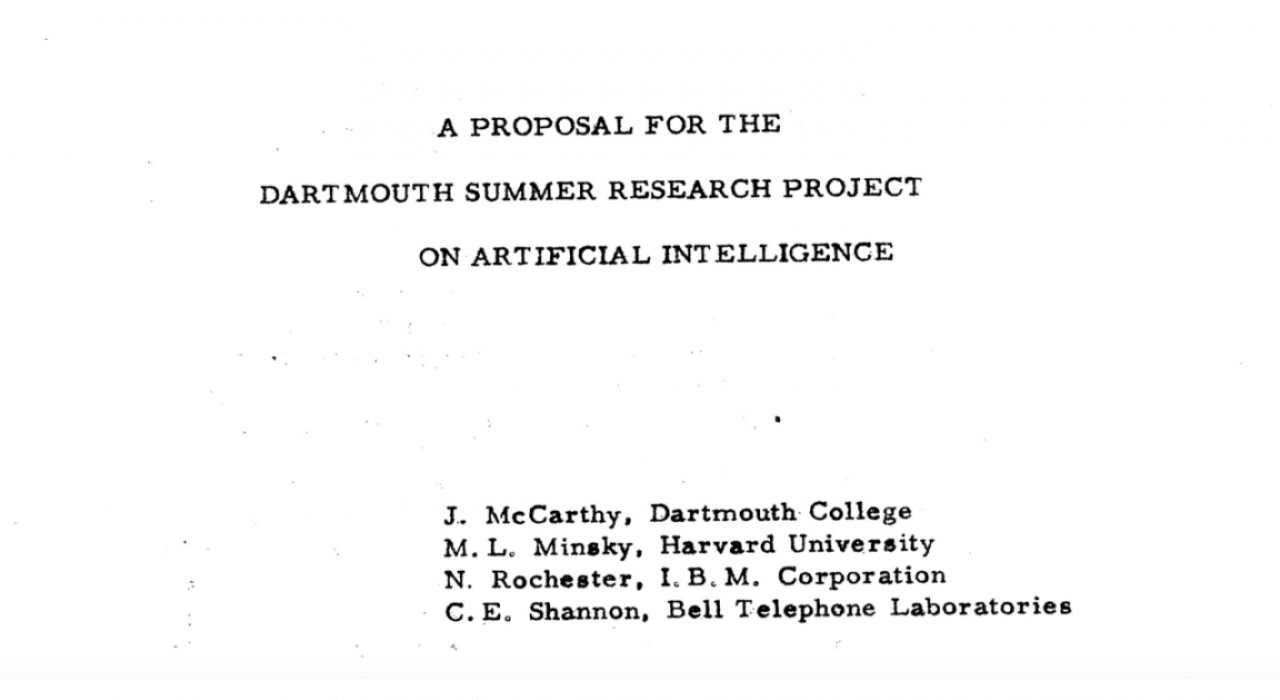

This is where the Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence was born. In the proposal, McCarthy wrote:

“We propose that a 2 month, 10 man study of artificial intelligence be carried out during the summer of 1956 at Dartmouth College… every aspect of learning or any other feature of intelligence can in principle be so precisely described that a machine can be made to simulate it.”

It was an audacious statement — equal parts optimism and daring. The term “artificial intelligence” itself was coined for this event. And so, that summer, the world’s first dedicated AI research meeting convened in Hanover, New Hampshire, in a small room where big dreams were scribbled onto blackboards.

The Summer of 1956

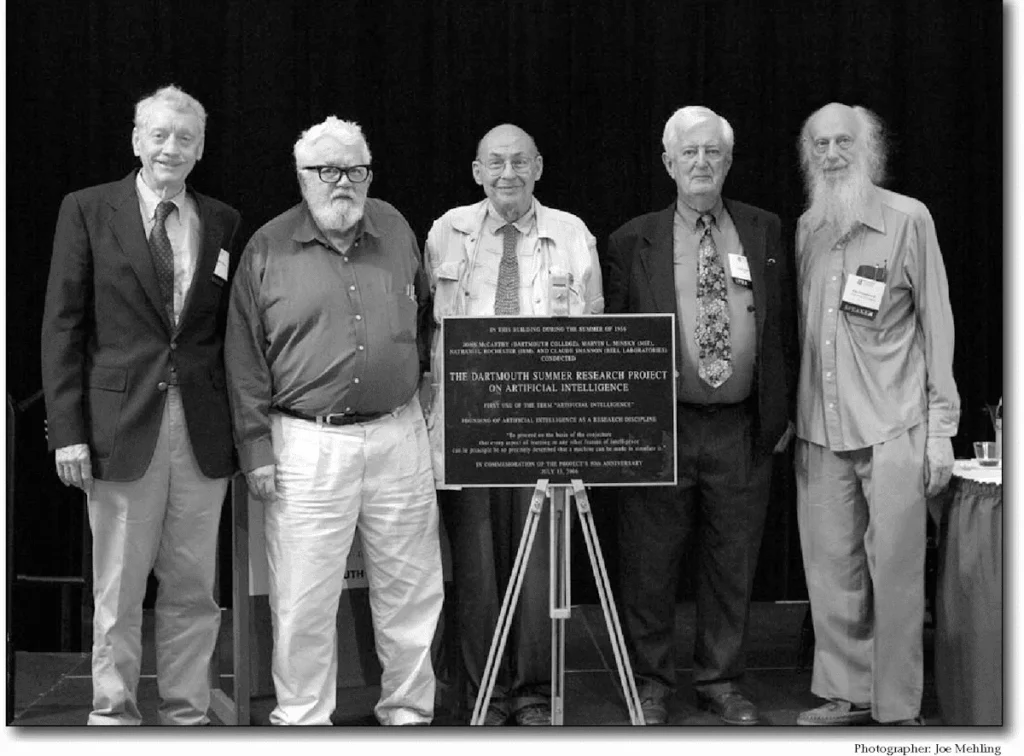

For several weeks that summer, a small group gathered in Hanover, New Hampshire, on the green lawns of Dartmouth College. The air was warm, the days long, and the conversations even longer. Attendance shifted as people came and went, but the core group remained:

- John McCarthy — the driving force behind the event, who would go on to create the LISP programming language and spend his life shaping AI research.

- Marvin Minsky — a young scientist from Harvard with an unshakable belief that machines could be made to think, later co-founding the MIT AI Lab.

- Claude Shannon — the mathematician and cryptographer from Bell Labs whose information theory had already transformed communications.

- Nathaniel Rochester — the chief architect of IBM’s 701 computer, eager to see how these bold ideas could become working systems.

They debated how a machine might understand language, how it could learn from experience, and whether symbolic reasoning — the manipulation of words and ideas — might capture something of human thought. They even explored the idea of self-improving programs, where a computer could rewrite its own code to get better at a task.

The People Who Lit the Spark

- John McCarthy — later called the “father of AI,” creator of the LISP programming language and a relentless advocate for AI research.

- Marvin Minsky — a visionary in cognitive science and robotics.

- Claude Shannon — the architect of information theory, who brought mathematical rigor to the discussion.

- Nathaniel Rochester — chief architect of the IBM 701, one of the first commercial computers.

Each brought a different skill set, but they shared the belief that thinking machines were possible — and that they were worth

Why Dartmouth Still Matters

The Dartmouth Conference didn’t produce a single breakthrough algorithm. It didn’t end with a working “thinking machine.” But it changed the conversation. Before Dartmouth, AI was an interesting idea; after Dartmouth, it was a research field.

Many of today’s AI systems — from voice assistants to translation tools to recommendation engines — can trace their lineage back to that summer in 1956. The dreams of McCarthy, Minsky, Shannon, and Rochester still echo in the labs and tech companies pushing AI forward today.

Next in the Series:

We’ll follow the story into the first wave of AI programs after Dartmouth — the early experiments that showed both the promise and the limits of machine intelligence.