The Question That Started It All: Can a Machine Think?

Before we had chatbots, recommendation algorithms, and self-driving cars, there was just a question.

If you were alive in the early 1900s, machines were not something you associated with thought.

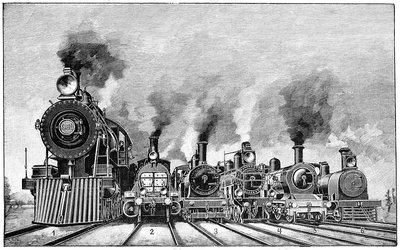

They were heavy, mechanical, and loud. Steam engines pulled trains, typewriters clacked in offices, and telephone operators connected voices across miles of copper wire. A machine could be impressive — even awe-inspiring — but thinking? That was the domain of people.

The very idea that a device might one day reason or think seemed like something from science fiction. Thinking was something only reserved for humans.

By the 1940s, people were starting to see machines differently.

The Second World War had forced scientists and engineers to invent faster and smarter tools. Instead of just doing the same simple job again and again, some new machines could follow a list of instructions and handle more complicated tasks.

This was a big change. Before, machines were like wind-up toys which only did one thing. Now, they could be told to do one thing and then another, in order, without human hands guiding every step.

Advances in electronics, wartime codebreaking, and the birth of programmable computers were changing how people thought about what machines could do.

If a machine could follow a complex set of instructions, what was stopping it from doing something more ambitious?

That’s where a young British mathematician named Alan Turing stepped in.

A Mind Ahead of Its Time

Alan Turing was no ordinary academic. He had a knack for approaching problems from angles that others overlooked. During World War II, Turing worked at Bletchley Park, Britain’s secret code-breaking centre, where he played a pivotal role in breaking the German Enigma code—a feat historians believe shortened the war by years. Even before that, he had been fascinated by the abstract idea of computation: the notion that a machine could follow logical rules to produce answers, just as a human might.

But for Turing, the war was only one chapter. His real obsession was a question he first put into writing in 1950:

“Can machines really think?”

Alan Turing

It sounds simple, but even today it’s a question that refuses to sit still. What do we mean by “think”? Is it solving a puzzle? Holding a conversation? Feeling joy or frustration?

Turing avoided arguing over definitions. Instead, he came up with a way to test the idea in practice.

The Imitation Game

In his paper “Computing Machinery and Intelligence”, Turing described a kind of role-play.

Instead of getting stuck on what “think” means — which is a messy, philosophical debate — he imagined a simple test anyone could try. He called this test The Imitation Game.

Here’s how it works:

Imagine you’re sitting in a room, typing messages back and forth with two other players. One is a person like you, and the other is a machine. You can’t see either of them — all you know is you’re chatting through a text-only setup.

Your job is to figure out which player is the human and which is the machine.

If you can’t tell the difference — if the machine’s replies are just as convincing as the human’s then, according to Turing, the machine could be said to be “thinking.”

We didn’t need to know whether machines could think exactly like us. We just needed to see if they could act enough like us to make the difference disappear.

It didn’t need to truly understand. It didn’t need feelings or imagination. It just needed to respond in a way that felt human.

Why it mattered?

In the 1950s, computers filled entire rooms. They didn’t learn. They didn’t adapt. They did exactly what they were told — nothing more, nothing less.

When Alan Turing introduced his test, he changed the way people thought about machine intelligence. Instead of debating what it means to think, he proposed a simple way to find out if a machine could act like a human so well that a person couldn’t tell the difference. These weren’t just questions about just computers. They were questions about what it means to be human.

This was powerful because it turned a difficult, philosophical question into something practical and measurable. The focus wasn’t on whether machines had feelings or consciousness. It was on whether they could behave intelligently enough in conversation to pass as human.

By shifting the question from “Can machines think?” to “Can machines imitate thinking?” Turing gave scientists a clear goal to work towards. It wasn’t about building a perfect human mind; it was about building machines that could interact like humans do.

From Hypothesis to Reality

Seventy years later, Turing’s thought experiment feels less like theory and more like a forecast.

Today’s AI systems can write stories, compose music, answer questions, and even joke — sometimes well enough to fool us, sometimes not. They haven’t “passed” the Turing Test in the purest sense, but they’ve gotten close enough to prove the idea was worth asking.

And yet, the question remains. Does acting like a human mean being like a human? Or is true thinking something no machine will ever touch?

In our next chapter, we step into the summer of 1956 — a turning point when “thinking machines” became more than an idea. At Dartmouth College, a small group of scientists gathered with a shared ambition: to lay the foundations of a brand-new field. It was here that artificial intelligence not only found its name but also its first roadmap.